|

|

|

||||||

|

Capone and His Era

Printable Version

Al Capone has become such a symbol of

the Italian American-as-gangster

that people forget to place him within an historical context.

Author and historian Giovanni Schiavo does so

in the following excerpt from his book,

"The Truth about the Mafia and Organized Crime in America."

There are certain things which should be said about Al Capone:

Capone represents the triumph of amoral intelligence over morally prescribed 'failure' when the opportunities to success are barred or limited in a community in which economic success is the ultimate goal.On December 30, 1918, Capone married in Brooklyn Mary Coughlin, the daughter of Michael and Bridge (Gorman) Coughlin, natives of Ireland. Shortly after that, he was called to Chicago to assist Johnny Torrio in running the various enterprises, primarily houses of prostitution, of his uncle, "Big Jim" Colosimo. It was not clear whether Prohibition at that time was in force. It was after the death of Colosimo in 1920, and especially after the wounding of Torrio in 1925, that Capone became a gang chieftain. The rest is too well known to be repeated here. Elmer L. Irey stated in "The Tax Dodgers" that according to Internal Revenue agent Madden, Capone was a "fathead," just a front for respectable businessmen who pulled the strings behind the scenes. Perhaps so. Judge John H. Lyle disagrees in "The Dry and Lawless Years" and adds that other investigators who had the opportunity to study Capone at close quarters felt the way he did. According to Judge Lyle, Capone was "keen-witted, forceful and crafty", but in all probability, he was a straw man for a powerful trust. That, too, may have been possible, although one must take Judge Lyle's opinions with a grain of salt in view of the not very wise statements he makes in his book about the Mafia, the Camorra and the Blackhand. A man in Judge Lyle's position had every opportunity to learn at first hand the difference between Mafia and Camorra, as well as between Mafia and Blackhand. |

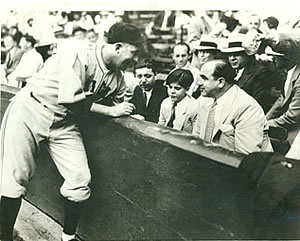

Capone, accompanied by his son and lawyer, is greeted by the Cubs' Gabby Hartnett at Wrigley Field, 1931. Edgar Lee Masters, with the genius and intuitiveness of the poet and the training of the historian, surveyed the field with an eagle eye and reached the conclusion that Capone had a brain as good as Rockefeller's or Insull's. Insull was the English-born utilities magnate who caused hundreds of thousands of people to lose more than $750,000,000 and possibly as high as two billion. According to Masters, all three men used their brains to the same end; furthermore, Capone, compared to Robin Hood, was like a condor compared to a kingfisher and Insull just an octopus lying behind a rock waiting to seize unwary fish swimming by. It is hard to extricate the truth from the rubble that surrounds Capone's legendary life, what with the exaggerations of admirers, defamers and hack writers, yet there is no doubt about Capone's keen intelligence, forcefulness and cunning. No man, in fact, could have ruled over an assemblage of the most unsavory, ruthless and ambitious characters of various nationalities in the history of Chicago for so many years, had he not possessed qualities that forced respect and obedience. Even from jail. Judge Lyle wrote that investigators who knew Capone felt that he could have been a successful businessman had he chosen to do so. That is true, provided America had not closed her doors in his face. All those stories about America as the land of opportunity should be relegated to the field of mythology. As Shaloo correctly said in his review of Saveth's "American Historians and European Immigrants," "anyone who honestly, if naively, believes that America ever was or will be an asylum or refuge for the weary and heavy laden, or that Emma Lazarus echoed the generous impulses of articulate and outstanding historians, will find this volume a superlative corrective." The Italians, like the other immigrants, especially the Jews, had to fight their way out of the slums and the status of economic, political and social inferiority in which the self-styled superior dominant classes tried to confine them. Some people resorted to fraud, Capone chose the gun. Capone was the product of America and of the American way of life, especially America's tradition of violence and disrespect of the law. He was one of those young men who saw his parents live a miserable life digging ditches or being exploited in a sweatshop, derided by hoodlums who lived apparently in affluence without doing an honest day's work. Quick-witted, surrounded by violence and corruption, he, too, learned that money was the key to almost everything in a hedonistic society, and joined the gangs. Living in a slum did not determine his future life. Other men living in the same neighborhood did not turn to crime, either because they feared the consequences or because there was no prejudice against them, or for other reasons. A quote from Al Capone, All-American: "I ain't Italian, I'm from Brooklyn!" |